Backward plannning

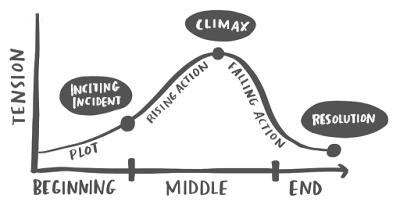

One of the main principles that shape the Literacy Approach is backward planning. Coined by Wiggins & McTighe (2005), I first heard about it from my colleague Oliver Meyer. What backward planning consists in is starting the planning of a unit of work from the end of the teaching unit. This means that my first thought when planning a literacy unit will be: what do I want my students to be able to do (or, in our case, produce) at the end of the unit? Will I want them to create a video tutorial for an arts and craft project, a poster explanation of a science experiment or a written description of students' favourite holiday-site? Depending on the kind of text I want them to be able to produce, and of the medium chosen for this production (visual, audiovisual, spoken or written), my students will need different skills, knowlegde and understandings. This means that, if I start my planning process with the end production rather than with the contents the syllabus - or, let's be honest, the textbook - have selected, I can be sure that what I work on with my students will be relevant and meaningful for them. They will be using everything dealt with in class, from the camera-angle to the structure of the how-to video via the necessary linguistic building blocks, for their final production, and know that, in so doing, they are likely to be successful.

In this sense, the Literacy Approach, as any learning planned from "the back" is, by nature, success- oriented, and this, for me, is a really important departure from most teaching. When we teach, and even more when we assess, we tend to be focused on what students are not able to do or what they do wrong. By changing the focus to building the skills and knowledge in my teaching that make it possible for my students to be successful, I am taking a more positive and constructive approach to teaching that is likely to transfer to students. In fact, when teachers plan in this way, they often find that students want to produce more, and are proud of their achievement. The teachers themselves are often surprised by what students are able to do, given the appropriate support and guidance.

Of course, for many teachers this way of planning is rather unsettling, because they have a syllabus to cover. Interestingly, in my experience, this syllabus is actually much less demanding than teachers think, and often a single literacy unit covers much more ground than a textbook unit, as skilful communication through text requires a great number of different elements, and what students learn in a meaningful context will probably be much more memorable than if learnt because "in May we will do the passive voice". How we can make sure that the literacy units we plan cover the established syllabus is dealt with in chapter 6 of the book 😊

Comments

Post a Comment